American Military Cemeteries in Europe

There are eight ABMC cemeteries in this section, six of these in France, and one each in England and Belgium, totaling 30,921 war dead, or 26% of recovered fallen from U.S. forces in World War I. At 11 a.m. on the 11th day of the 11th month of the year 1918, the Great War ended. Every year on this date (November 11, 11h00) many towns hold memorial ceremonies, especially Ypres (Ieper), Belgium, which saw some of the bloodiest fighting of the war. Roughly 500,000 soldiers from both sides are buried in 170 cemeteries in this region of Flanders, thus it is appropriate to kick-start this section with the American cemetery nestled in this poetic corner of the province.

![]()

BELGIUM

1) Flanders Field American Cemetery

Of the 368 American soldiers interred here, six of these warriors died on November 11th,

the last day of the war! At Flanders Field American Cemetery, 6 acres in size, 368 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom gave their lives for the liberation of Belgium. Of the 368 fallen American soldiers, some 240 of their number died within the final two weeks of the war (i.e. Oct. 27—Nov. 11, 1918), and more than half of these war dead were from three states: Ohio (58), Pennsylvania (38), and California (28). Devastatingly, *six of these warriors died on November 11th, the last day of the war! (*One each from CA, IL, MN, NY, and two from OH — Pvt. William T. Fossum from MN is pictured.)

At Flanders Field American Cemetery, 6 acres in size, 368 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom gave their lives for the liberation of Belgium. Of the 368 fallen American soldiers, some 240 of their number died within the final two weeks of the war (i.e. Oct. 27—Nov. 11, 1918), and more than half of these war dead were from three states: Ohio (58), Pennsylvania (38), and California (28). Devastatingly, *six of these warriors died on November 11th, the last day of the war! (*One each from CA, IL, MN, NY, and two from OH — Pvt. William T. Fossum from MN is pictured.)

At this tranquil site, formerly a battlefield, the fallen are aligned in four rectangular plots, each consisting of 92 graves, surrounding a tall stone chapel that marks the core of the memorial park. Engraved inside the chapel are the names of an additional 43 missing comrades to be honored.

During the Great War, the Flanders region of Belgium suffered destruction beyond belief. A battlefield so grotesque that a Hollywood director would struggle to bring home the war’s flesh-rotting stench to the audience. Thousands of men were slaughtered for mere yards of tactical gain. Death permeated a hellish wasteland of automobile-sized craters left by pounding artillery; disfigured stumps remained where full-bodied trees once blossomed; an eerie moonscape cut by zig-zagging trench fortifications that paralleled mounds of shell-blasted debris and rusted barbed wire. Human body parts littered the fields that transformed into a sea of muddy graves when it rained while bloating already unbearable dugouts for the fatigued, traumatized soldiers who remained. Miraculously, the only survivor, budding through the muck year after year in springtime, was the heavenly poppy.

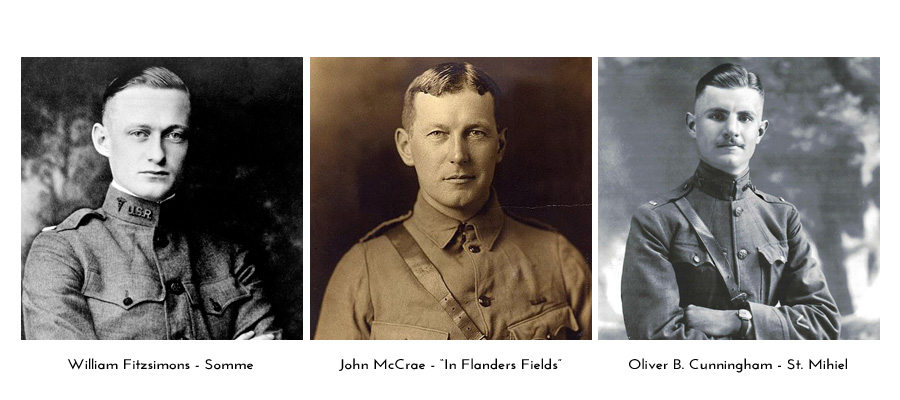

Lt. Col. John McCrae, M.D. (pictured in the slider at the top of the page), with the Canadian army, wrote a touching poem in memoriam to the brave soldiers who fought and died “In Flanders Fields.”

Fittingly, Flanders Field American Cemetery takes its name from the poem. As a tribute, every year during the Memorial Day ceremony, John McCrae’s renowned words are recited:

“In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

“We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved, and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

“Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.”

McCrae died of pneumonia on January 28, 1918 (age 46), after four years of dedicated service on the Western Front. He is buried in Wimereux Communal Cemetery, 5 km north of Boulogne, and 30 km south of Calais, France.

On May 30, 1927 Charles Lindbergh—famed American aviator and pioneer—flew over Flanders Field American Cemetery in the Spirit of St. Louis to salute his fallen countrymen and drop poppies on the Memorial Day ceremonies being held below. He did this just 9 days after he completed his historic, solo trans-Atlantic flight.

To get there; Flanders Field American Cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located on the south edge of the town of Waregem, Belgium, along the Lille-Gent (E17) expressway (exit N382 and follow small American Cemetery signs)—15 km northeast of Kortrijk (Courtrai), 280 km north of Paris, and 85 km west of Brussels.

Join our Belgium Beer & Battlefields tour and visit Flanders Field American Cemetery with Harriman

![]()

ENGLAND

2) Brookwood American Cemetery

At Brookwood American Cemetery, 4.5 acres in size, 468 heroes rest peacefully—whom “died from all manner of cause in World War I.” Engraved inside the chapel are the names of an additional 563 missing comrades to be honored, including all 114 hands from the Coast Guard cutter the USS Tampa, sunk in the Bristol Channel by a German sub in September 1918. Brookwood American Cemetery lies within the vast civilian Brookwood Cemetery—cars may drive through to reach the ABMC memorial site. Of interest are nearby military cemeteries and monuments memorializing soldiers from the British Commonwealth and other Allied nations.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located on the south side of the township of Brookwood, in Surrey, roughly 28 miles southwest of London. Railers, you can catch a train from London (Waterloo station) to Brookwood in less than an hour—the burial ground is some 300 yards southwest from the station.

![]()

FRANCE

3) Suresnes American Cemetery

...the memorial park affords an unforgettable view of Paris, punctuated by the Eiffel TowerAt Suresnes American Cemetery, 7 acres in size, 1,565 heroes (men and women) rest peacefully, many of whom died from sickness or battlefield injuries while admitted to the American military hospital in Paris. Among the dead buried here is a pair of brothers, seven nurses (two were *sisters), and 24 unknown soldiers from World War II. Engraved on bronze tablets in the chapel are the names of an additional 974 missing comrades to be honored. In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson came here and fittingly dedicated the cemetery on Memorial Day. Inscribed above the entrance of the neoclassic chapel are these poignant words: “PEACEFUL IS THEIR SLEEP IN GLORY.”

(*The Cromwell twins, Dorothy and Gladys—plot B, row 18, graves 22 & 23—were civilian volunteers with the American Red Cross in France. The pain and suffering they witnessed, the horrors of war, the seemingly endless stream of wounded arriving from the front was too much to bear. Mentally depleted, both 30-something women committed suicide on January 19, 1919, just two months after the end of the war, and were buried here at Suresnes American Cemetery with full military honors.)

Situated on the historically rich slopes of Mont Valérien, the memorial park affords an unforgettable view of Paris, punctuated by the Eiffel Tower. In earlier times, Mont Valérien—known as Mont Calvaire—was the site of a hermitage that regularly attracted religious pilgrimages. Part of the hermitage consisted of a guest house, which was often visited by Thomas Jefferson during his five-year ambassadorship to France (1785-89). Around 1813, Napoleon requested that a fort be built here. During World War II, Nazi troops occupied the fort and dreadfully executed some 4,500 political prisoners and members of the Resistance. Commemorating the sacrifice of those who died under Hitler’s bloody reign, the French people erected a monument along the fort’s south wall. Mont Valérien, hallowed ground for both French and American peoples, has come to symbolize strength through freedom, democracy over tyranny. A must-visit for any traveler to Paris!

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located in the suburb of Suresnes, 9 km west of downtown Paris. It can be reached by car but your best bet is by train which departs regularly from Gare St. Lazare to the Suresnes Mont Valérien station (then 10-min walk: exit Hospital Foch, go right and straight up the road Rue du Calvaire to the traffic-lighted intersection at Boulevard Washington, turn right and the cemetery’s white-marble headstones come into view on the hillside. The gilded wrought-iron entrance gate is just ahead on the left. Stunning, no?).

4) Aisne-Marne American Cemetery

This exceedingly tranquil burial ground is located on the former battlefield where gallant members of the

American Expeditionary Forces, affectionately known as “doughboys,” fought and diedAt Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, 42 acres in size, 2,289 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom fought locally at Belleau Wood, as well as in the nearby Marne Valley in the summer of 1918. Engraved inside the memorial chapel are the names of an additional 1,060 missing comrades to be honored.

Consecrated on May 30, 1937, this exceedingly tranquil burial ground is located on the former battlefield where gallant members of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), affectionately known as “doughboys,” fought and died. At the head of the cemetery and standing more than 80-feet-tall, the Romanesque-style chapel rests upon the former front-line trenches dug by the U.S. 4th Marine Brigade as part of the defense of Belleau Wood against a German offensive (June 1918) aimed at seizing Paris to win the war. The Marines held their ground in the desperate fight against an overwhelming enemy force, essentially putting the brakes on the German offensive and saving Paris. In recognition of the courageous actions of the 4th Marine Brigade, the French renamed the surrounding forest “Bois de la Brigade de Marine” (Woods of the Marine Brigade). Many vestiges of the war still remain in these dense, storied woods. Note: Right of the chapel entrance is a puncture in the stonework made by the shell of a German anti-tank gun firing on French armored positions in 1940 during World War II.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located on the edge of the village of Belleau, 10 km northwest of Château-Thierry, and 80 km northeast of Paris. Railers, you can catch a train from Paris (Gare de l’Est) to Château-Thierry in one hour, then taxi (15 min). Drivers, (consider also visiting nearby Oise-Aisne Cemetery), from Paris to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery you have two options: (1) 100 km: drive the much-slower but free-of-charge N3 west out of Paris to Meaux, then route D603 for most of the way changing to D1003 at Montreuil-aux-Lions. Some 7 km beyond Montreuil-aux-Lions turn left following the sign to Lucy-le-Bocage (route D82; here you pick up the sign to the cemetery). After a handful of kilometers turn right on the D9 to Belleau and the cemetery entrance (en route passing the unremarkable German cemetery). (2) 80 km: take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) direction Reims/Metz and exit at Montreuil-aux-Lions (sortie 19), then follow signs through Montreuil-aux-Lions (direction Château-Thierry) and about 7 km outside of town turn left following the sign to Lucy-le-Bocage (route D82; here you pick up the sign to the cemetery). After a handful of kilometers turn right on the D9 to Belleau and the cemetery entrance (en route passing the unremarkable German cemetery).

![]()

Harriman hand-drew the following maps to give you a better idea of where the cemeteries are located within France, England, and Belgium.

![]()

War summary, 1917-18:

The following *passage comes from the St. Mihiel Cemetery “visitor booklet” (*except that I added some minor edits and references to cemetery listings to help give you a better understanding of their locale and battle timeframe). Additionally, I felt the following passage would give you a good overview of the front line on the Western Front during the last two years of the war as well as to summarize the mission of the American forces and set the scene of significant battles that are now (in most cases) the hallowed ground on which the ABMC cemeteries are located.

Toward the end of 1916, French and British commanders on the Western Front were optimistic concerning a successful conclusion to the war in 1917. Except for the loss of Romania, events during 1916 had appeared to be working in favor of the Allies, who had numerical superiority on all fronts.

As if to reinforce Allied optimism, the Germans began withdrawing some of their forces north of Paris to prepared positions approximately 20 miles to the rear that could be held by fewer divisions. These defensive positions were later to be known as the Hindenburg Line [location of Somme American Cemetery, No. 6]. The Russian Revolution broke out while the German withdrawal north of Paris was still in progress. The revolution delivered a serious blow to Allied plans, as the Russian Army had been counted upon to keep German troops occupied on the Eastern Front. Although the Russian Army did not collapse immediately, it was apparent that it soon would.

On 6 April 1917, the United States entered World War I with no modern equipment and less than 200,000 men stationed from the Mexican border to the Philippines. It would take longer for the U.S. to mobilize its troops and prepare them for combat than for the Russian Army to disintegrate. Despite this realization, the French and British Armies began the offensives that had been planned on the Western Front prior to the Russian Revolution in March. The initial British assault began on 9 April, followed by a French offensive on 16 April. Quickly, the French offensive turned into a disaster, leaving the British Army to shoulder the main burden of the war until French forces could reorganize and recuperate. On the Eastern Front, the Russians started to attack but were promptly driven back. Shortly thereafter, an assault by the Germans in the north caused the Russians to seek an armistice. Although the treaty between Germany and Russia was not signed until March 1918, the Germans began moving divisions from Russia to France as early as November 1917, in an attempt to end the war before sufficient American troops could be brought into action to turn the tide.

As a consequence, the beginning of 1918 looked far worse for the Allies than the beginning of 1917. To take advantage of the troops that had been moved to France from the east, the Germans launched a series of five powerful offensives on 21 March 1918. The first two offensives caused considerable concern among the Allies who vehemently contended that if American soldiers were not sent immediately to replace the depleted ranks of their units, the war would be lost. General John J. Pershing (pictured), Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), refused to allow his men to be used piecemeal. The push was on and in a surprisingly short time Pershing organized, trained and equipped the AEF into effective fighting units. When the French Army found itself in desperate need of assistance during the third and fifth German drives, General Pershing offered American troop units to halt the advancing enemy. Informally known as “doughboys,” the outstanding achievements of U.S. troops sent to the aid of the French Army are recorded at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery [No. 4] and at the Chateau-Thierry Monument.

As a consequence, the beginning of 1918 looked far worse for the Allies than the beginning of 1917. To take advantage of the troops that had been moved to France from the east, the Germans launched a series of five powerful offensives on 21 March 1918. The first two offensives caused considerable concern among the Allies who vehemently contended that if American soldiers were not sent immediately to replace the depleted ranks of their units, the war would be lost. General John J. Pershing (pictured), Commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), refused to allow his men to be used piecemeal. The push was on and in a surprisingly short time Pershing organized, trained and equipped the AEF into effective fighting units. When the French Army found itself in desperate need of assistance during the third and fifth German drives, General Pershing offered American troop units to halt the advancing enemy. Informally known as “doughboys,” the outstanding achievements of U.S. troops sent to the aid of the French Army are recorded at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery [No. 4] and at the Chateau-Thierry Monument.

When the last great German offensive commenced on 15 July east of Chateau-Thierry, it was promptly repulsed in a severe struggle in which American troop units played a leading part. Quickly, a U.S.-French counteroffensive was launched on 18 July at Soissons. The highly successful three-week battle that followed, known officially as the “Aisne-Marne Offensive” (but called the “Second Battle of the Marne” by the Allied commander Marshal Foch), marked the turning point of the war.

Determined to keep the enemy on the defensive, Marshal Foch, at a conference on 24 July, planned a series of strong offensive operations to maintain the initiative and give the enemy no respite or opportunity to reorganize. Following completion of the Aisne-Marne Offensive, the British, assisted by the French, were given the mission of conducting an offensive in the Amiens sector where the enemy had made great gains in March and April.

At this conference, General Pershing chose the St. Mihiel sector for an American offensive [the site of today’s St. Mihiel American Cemetery, No. 7]. The objective of the offensive was a German salient projecting 16 miles into the Allied line. Roughly shaped like a triangle, the salient ran from Verdun in the north, south to St. Mihiel, and east to Pont-a-Mousson. In addition to its natural defensive advantages, the salient protected the strategic rail center of Metz and the Briey iron basin so vital to the Germans as a source of raw material for munitions. It also interrupted French rail communications and represented a constant threat against Verdun and Nancy. Reduction of the salient was imperative before any large Allied offensive could be launched against Briey and Metz or northward between the Meuse River and Argonne Forest.

At the conference, General Pershing insisted that the attack be an AEF operation with its own sector, under the separate and independent control of the American commander. When the decision was made, there were over 1,200,000 American soldiers in U.S. troop units widely scattered throughout France, either serving with French or British armies or training in rear areas. In view of the splendid record that so many of the U.S. units had already achieved in combat, the French and British were forced to agree that a separate U.S. Army should be formed, although they requested that U.S. divisions continue to be permitted to fight with their armies.

The order creating the United States First Army became effective on 10 August 1918. On 30 August, the U.S. First Army took over the St. Mihiel sector. After a series of conferences, the Allies agreed that the St. Mihiel attack should be limited to a reduction of the salient, following which the U.S. First Army would undertake a larger scale offensive on the front between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest. With the attack at St. Mihiel scheduled for 12 September, this would require winning an extraordinarily swift victory, then concentrating an enormous force to launch a still greater operation 40 miles away, within just two weeks! Never before on the Western Front had a single army attempted such a colossal task.

At 0500 hours, 12 September 1918, following a four-hour bombardment by heavy artillery, the U.S. I and IV Corps composed of nine U.S. divisions, began the main assault against the southern face of the salient, while the French II Colonial Corps made a holding attack to the south and around the tip of the salient. A secondary assault by the U.S. V Corps was made three hours later against the western face of the salient. Reports were soon received that the enemy was retreating. That evening, the order was issued for U.S. troops to press forward with all possible speed. By the dawn of 13 September, units of the U.S. IV and V Corps met in the center of the salient, cutting off the retreating enemy. By 16 September, in an astounding victory achieved by dogged determination and tenacious fighting, the entire salient had been eliminated! Throughout these operations, the attacking forces were supported by the largest concentration of Allied aircraft ever assembled. The entire reduction of the salient was completed in just four days by which time some of the divisions involved had already been withdrawn to prepare for the Meuse-Argonne battle [site of today’s Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, No. 8].

![]()

FRANCE

5) Oise-Aisne American Cemetery

The dead buried here represent all of the-then 48 states and the District of Columbia At Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, 36 acres in size, 6,012 heroes rest peacefully, the second largest burial of U.S. military dead in Europe from World War I—most of whom fought and died here in the summer of 1918 while defending the German offensive aimed at capturing the French capital and effectively winning the war. Engraved within the rectangular stone chapel are the names of an additional 241 missing comrades to be honored. The dead buried here represent all of the-then 48 states and the District of Columbia. One soldier representing New York, Sergeant Joyce Kilmer (plot B, row 9, grave 15), a leading poet of his time, was sadly killed by a German sniper (on July 30, 1918) some 800 meters from his headstone. Back home in the USA, to honor Kilmer’s memory, parks, streets, squares and schools bear his name.

At Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, 36 acres in size, 6,012 heroes rest peacefully, the second largest burial of U.S. military dead in Europe from World War I—most of whom fought and died here in the summer of 1918 while defending the German offensive aimed at capturing the French capital and effectively winning the war. Engraved within the rectangular stone chapel are the names of an additional 241 missing comrades to be honored. The dead buried here represent all of the-then 48 states and the District of Columbia. One soldier representing New York, Sergeant Joyce Kilmer (plot B, row 9, grave 15), a leading poet of his time, was sadly killed by a German sniper (on July 30, 1918) some 800 meters from his headstone. Back home in the USA, to honor Kilmer’s memory, parks, streets, squares and schools bear his name.

Of Kilmer’s many literary works, his most famous is a simple poem called Trees:

“I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.”

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located 2 km east of the town of Fére-en-Tardenois, 25 km northeast of Château-Thierry, 40 km west of Reims, and 100 km northeast of Paris. Railers, difficult to reach, taxis are not available from Fére-en-Tardenois station. Drivers, (consider also visiting nearby Aisne-Marne Cemetery), from Paris to the Oise-Aisne Cemetery take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) east direction Reims/Metz and exit at sortie 20, Château-Thierry (80 km), then turn left onto the D1 north direction Soissons. Ahead, midway through the town of Rocourt-Saint-Martin, follow the directional sign right to Fére-en-Tardenois (D310), and midway through Fére-en-Tardenois follow sign right to the cemetery (D2).

6) Somme American Cemetery

By the end of the battles, the U.S. II Corps suffered an astounding 13,500 casualties while its soldiers were

awarded 19 Medals of Honor!At Somme American Cemetery, 14 acres in size, 1,844 heroes rest peacefully—engraved within the small memorial chapel made of white Vaurion stone are the names of an additional 333 missing comrades to be honored—most of whom fought and died with the U.S. 27th and 30th divisions, II Corps, during the first and second battles of the Somme (March-Nov 1918), which accounted for some of the bloodiest fighting of the war.

The advancement of armies in the Somme measured in mere meters at the cost of thousands of lives. For the Americans, the 107th Infantry Regiment, 27th Division, suffered 995 casualties on the first day alone of the Hindenburg offensive in the Somme, amounting to the country’s single largest regimental loss of the war. By the end of the battles, the U.S. II Corps suffered an astounding 13,500 casualties! Its soldiers were showered with praise and tributes for valor, distinguished awards and citations, including 19 Medals of Honor.

Today, amid gently rolling farmland in northern France, the land formerly comprising the German Hindenburg Line (multitiered trench fortifications) is the setting of the picturesque Somme American Cemetery. Among the glorious rows of headstones are three Medal of Honor recipients, as well as nurse Helen Fairchild (pictured) from Pennsylvania (plot A, row 15, grave 13) who died as a result of lending her gas mask to a wounded soldier, and brothers James and Harmon Vedder, buried side by side (plot D, row 2, graves 2 & 3), whose deaths inspired the creation of the Gold Star mothers. Sadly, Harmon died (on Nov 5, 1918) six days prior to the end of the war. Also interred here is 1st Lt. William T. Fitzsimons (pictured in the slider at the top of the page), the first American officer killed in the war (plot B, row 9, grave 14). Graduate of the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Dr. Fitzsimons was stationed at a field hospital in France tending to wounded soldiers when Germans bombed the medical facility in a cowardly air-raid on September 4, 1917.

Today, amid gently rolling farmland in northern France, the land formerly comprising the German Hindenburg Line (multitiered trench fortifications) is the setting of the picturesque Somme American Cemetery. Among the glorious rows of headstones are three Medal of Honor recipients, as well as nurse Helen Fairchild (pictured) from Pennsylvania (plot A, row 15, grave 13) who died as a result of lending her gas mask to a wounded soldier, and brothers James and Harmon Vedder, buried side by side (plot D, row 2, graves 2 & 3), whose deaths inspired the creation of the Gold Star mothers. Sadly, Harmon died (on Nov 5, 1918) six days prior to the end of the war. Also interred here is 1st Lt. William T. Fitzsimons (pictured in the slider at the top of the page), the first American officer killed in the war (plot B, row 9, grave 14). Graduate of the University of Kansas School of Medicine, Dr. Fitzsimons was stationed at a field hospital in France tending to wounded soldiers when Germans bombed the medical facility in a cowardly air-raid on September 4, 1917.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) neighbors the village of Bony, 2 km west of route D1044, 20 km north of St. Quentin and 160 km north of Paris. Drivers, from Paris take the A1 tollway (péage, blue signs) direction Lille (about 110 km) and exit at No. 13 (Péronne). Follow the green signs (some 15 km) direction St. Quentin (E44) and as you’re skirting the town of Vermand take the road (D33) left to Bellenglise. At the end of Bellenglise go left direction Cambrai (D1044). About 2 km past Bellicourt turn left to Bony and the cemetery (Mémorial Américain).

7) St. Mihiel American Cemetery

One of those young soldiers is Captain Cunningham from Illinois who died on Sept. 17, 1918 — his 24th birthday!At St. Mihiel American Cemetery, 40 acres in size, 4,153 heroes rest peacefully—infantry and airmen, most fought locally in the offensive against the St. Mihiel salient in September 1918. Inscribed on the walls of the map room across from the chapel are the names of an additional 284 missing warriors to be honored. St. Mihiel Cemetery, another magnificent gem in the pristine collection of ABMC memorial parks dedicated to the courageous “doughboys” of the First World War, is positioned almost at the heart of the salient where the majority of war dead interred here gave their lives.

Marking the center of the grounds a circular garden is crowned by a large sculpted sundial in the shape of an American eagle. Chiseled into its base is a promise made by the U.S. commander John J. Pershing: “TIME WILL NOT DIM THE GLORY OF THEIR DEEDS.” Nearby, the statue of a young American soldier stands pensively in his field uniform with trench helmet in hand before a considerable stone cross. Engraved above his head are the Latin words meaning, “HE SLEEPS FAR FROM HIS FAMILY IN THE GENTLE LAND OF FRANCE.”

One of those young American soldiers is Captain Oliver Baty Cunningham (pictured in the slider at the top of the page) from Illinois (plot C, row 13, grave 18), who died on September 17, 1918—his 24th birthday! Mrs. Cunningham was so distraught about her son’s death that she traveled to Thiaucourt, France for a period to be near him. While there, she gave charitably to help restore the parish church to include the purchase of three new bells as well as to sponsor the reconstruction of the town hall that had been reduced to rubble. A graduate of Yale University (class of 1917) and member of the 15th Field Artillery Regiment (2nd Div, AEF), Captain Cunningham was the only officer of his regiment to be killed in action during the war. On September 17, 1918, Cunningham was serving as a forward observer for his unit when an enemy shell landed on his position. “For repeated acts of extraordinary heroism in action” … and “with utter disregard for his personal safety,” Oliver Baty Cunningham posthumously received the Distinguished Service Cross—the second highest military decoration that the U.S. Army can bestow upon one of its members. In his honor, the Oliver Baty Cunningham Memorial Publication Fund bears his name at Yale University Press, and on the wall of the battle-scarred parish church at Thiaucourt a plaque reads that the steeple bells are dedicated to the memory of “Captain Oliver Baty Cunningham … who gave his life for his country and for France.” Adjacent to the church stands a monument featuring two larger-than-life statues of an American doughboy and a mustached French soldier clasping hands, symbolizing the great bond the two countries share, both of friendship and fraternal military order.

Another fascinating aspect about this part of the war, is the U.S. Army Air Service. We know the U.S. Air Force (USAF) today as the world’s largest and most sophisticated, having stealth bombers and supreme fighter-jet technology. But where did it all begin, i.e. where did American pilots first take to the sky in large numbers to fight in a combat-support role? During the battle to reduce the St. Mihiel salient, American forces for the first time in history threw in the bulk of its nascent air service to join the offensive with Allied squadrons, i.e. French and British. In a coordinated effort, pilots were instructed to fly behind enemy lines to gather intelligence and support the advance of ground troops by strafing German positions. All told, more than 1,400 Allied aircraft took part in the battle of St. Mihiel, with the U.S. Army Air Service playing a significant role in its astoundingly swift success. The air phase of the battle was directed by none other than General William (“Billy”) Mitchell, often regarded as the father of the USAF, a brash leader and man of action whose passionate yet controversial preachings calculated that strategic air power would dominate future warfare, which frequently put him at odds with his skeptical superiors, including then U.S. president Calvin Coolidge. Ultimately, because of his candidness denouncing the course of official government policy, Mitchell was demoted in rank and eventually court-martialed with loss of pay for so-called acts of insubordination. Disgraced, Mitchell resigned his position from the military in 1926. After his death in 1936, however, Mitchell’s vision of airborne supremacy was proven to be correct after the advent of World War II and the air attack over Pearl Harbor. Mitchell was vindicated and posthumously honored like no other; his rank of general was fully restored, the B-25 Mitchell bomber was named after him, as well as roads, schools and airports across the nation (particularly in his home state of Wisconsin), but arguably most important of all President Roosevelt in 1942 petitioned Congress to award Mitchell the Congressional Gold Medal—“In recognition of his outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of American military aviation”—to which he was bestowed in 1946.

But Billy was not the only aviation enthusiast in the family; his brother too joined the U.S. Army Air Service. Unlike Billy, however, 1st Lt. John L. Mitchell mournfully did not survive the war and is buried here at St. Mihiel American Cemetery (plot D, row 1, grave 4).

Other notable U.S. airmen who made the supreme sacrifice for their country and lie forevermore in this pastoral region of Lorraine, France, are 2nd Lt. Franklin B. Bellows (plot B, row 23, grave 5) from Illinois of the 50th Aero Squadron who gave his name to Bellows Field in Hawaii; 2nd Lt. Samuel R. Keesler Jr. (plot C, row 13, grave 20) from Mississippi of the 24th Aero Squadron who gave his name to Keesler AFB in Biloxi, MS; 1st Lt. John J. Goodfellow Jr. (plot D, row 12, grave 28) from Texas of the 24th Aero Squadron who gave his name to Goodfellow AFB in San Angelo, TX.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located on the western edge of the town of Thiaucourt, roughly 45 km southeast of Verdun, 37 km southwest of Metz, and 300 km east of Paris. Drivers, from Paris take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) east direction Metz and exit at (sortie 32) Fresnes-en-Woëvre. (From here the cemetery is about 25 km: Head direction Pont á Mousson [D908] and at the junction in the town of Fresnes-en-Woëvre turn left [D904] continuing toward Pont á Mousson. Ahead, after the village of Beney-en-Woëvre, the cemetery is on the right.) Note: When planning a trip to this part of France, consider allocating a day to visit nearby Verdun and its battlefields and monuments, e.g. Fort Douaumont, Fort Vaux, Trench of Bayonets, National Cemetery, Douaumont ossuary.

8) Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery

Here rests the largest burial of U.S. war dead in Europe, nine of whom were awarded the Congressional

Medal of HonorAt Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, 130 acres in size, 14,246 heroes rest peacefully (totaling the largest burial of U.S. war dead in Europe), most of whom fought locally in the *Meuse-Argonne in the fall of 1918. Engraved on wall panels outside the memorial chapel are the names of an additional 954 missing comrades to be honored.

*The Meuse-Argonne Offensive is the largest battle ever fought by U.S. troops in American history. More than 1 million U.S. soldiers took part in a six-week (Sept. 26—Nov. 11) series of exhaustive counter-offensives, compelling the Germans to seek an end to the war that became final on November 11, 1918. By the time the guns had silenced and the smoke lifted over the Meuse-Argonne, the Americans had suffered more than 100,000 casualties! Of the 118 soldiers awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor during World War I, nine are buried here—a testament to the severity and sacrifice, bravery and brutality, witnessed in this part of otherwise bucolic France. One of them, Freddie Stowers from South Carolina (plot F, row 36, grave 40), is the only African American recipient from the First World War. He died September 28, 1918 while contributing to the capture of Hill 188 against considerable enemy forces in entrenched positions.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located at the village of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, 40 km northwest of Verdun and 245 km east of Paris. Drivers, from Paris take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) east direction Metz and exit at No. 29.1, Clermont-en-Argonne. (From here the cemetery is about 35 km.) Drive through Auzéville (D998), Clermont, Neuvilly (D946), and Varennes (where King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were caught in their escape from Paris before being sent back and eventually guillotined; midway through Varennes you’ll pass the WWI Argonne Museum and the impressive and imposing Pennsylvania monument erected to preserve the memory of the Keystone State’s sons and daughters who fell during the Great War). Follow cemetery signs through Varennes (D946) and a few kilometers outside of town follow them right (D998) all the way through Romagne-sous-Montfaucon to the awe-inspiring cemetery. Note: When planning a trip to this part of France, consider allocating a day to visit nearby Verdun and its battlefields and monuments, e.g. Fort Douaumont, Fort Vaux, Trench of Bayonets, National Cemetery, Douaumont ossuary). Lastly, 10 km from the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery, stop in at the Montfaucon Monument and climb the 234 steps to the observation platform for breathtaking vistas of the former battlefield.

End of World War I cemeteries

That’s a wrap, folks! I hope you enjoyed reading about our gallant sons and daughters and now have a desire to visit an ABMC memorial park overseas. Please tell your friends and family; let’s get them involved too.

Click to go to Lest We Forget: World War Two

Click to go to the introduction of Lest We Forget

![]()

I’ll conclude this page with a moving message:

As you may already know, my annual research journeys me through Europe 10-12 weeks of each year to explore scenic and storied and unassuming sites, such as the war memorial in the medieval town of Dinkelsbühl, Germany, where I found these fitting words:

Der Toten Vermächtnis: Achtung des Lebens! “Legacy of the Dead: Respect Your Life!”

![]()

If you haven’t already, watch this five-minute ABMC production called Fields of Honor

(Last updated January 2017)