American Military Cemeteries in Europe

The United States officially entered World War II after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. This unprovoked aggression sealed the ruinous fate of the Pacific island nation within four years, including Hitler’s war machine in Europe. Some 16 million Americans answered the call of duty to serve their nation and fight oppression; 405,399 of these sacrificed their lives and nearly one-fourth of their number still remain in Europe, some resting only meters from where they fell.

In this section there are 14 awe-inspiring cemeteries typified by multi-acre landscaped gardens and breathtaking monuments made of granite, marble and bronze. Of these, one is in England, five in France, two in Italy, one in Luxembourg, one in Holland, two in Belgium, one in North Africa, and one in the Philippines. On this hallowed ground lie 93,213 American heroes—additionally there are the names of 55,862 missing comrades to be honored.

(Note: The last two WWII cemeteries listed in this section are located outside of Europe. Perhaps one is near a destination you’ll be visiting in the future.)

They died, so that you may live!It is obvious by the staggering numbers of war dead that freedom should not be taken for granted, and we owe our deepest gratitude to the hundreds of thousands of altruistic individuals who, for the sake of God and country, stared death in the face and sacrificed their most precious gift.

It was the everyday store clerk, tailor, factory worker, blacksmith, to name a few, who—as ordinary men in the prime of their lives—were certainly scared as hell as they marched into battle. The eyes of the world were upon these 20th-century crusaders and they achieved extraordinary deeds, fighting with uncommon valor for the God-given right to free will. Those who survived came home, too humble to tell us their stories, and built the American Dream. A great nation was forged and we are their privileged heirs.

Ask any veteran about the heroes they fought with and they’ll tell you about their comrades who stayed behind; the ones who didn’t survive the day to tell their tale. Tears well in the eyes; faces contort; stories abound as happy thoughts resurrect these posthumous heroes. Veterans take solace in the fact that their buddies will always remain ageless, radiating youth with a bright smile as they march off into an eternal sunset.

I can wholeheartedly say that when you visit an ABMC cemetery and stand amid the sweeping rows of white-marbled headstones, you will undeniably be among the greatest of company, a pantheon of heroes. They died, so that you may live!

Join our Belgium Beer & Battlefields tour and visit the cemeteries Luxembourg and Flanders Fields with Brett Harriman

ENGLAND

9) Cambridge American Cemetery

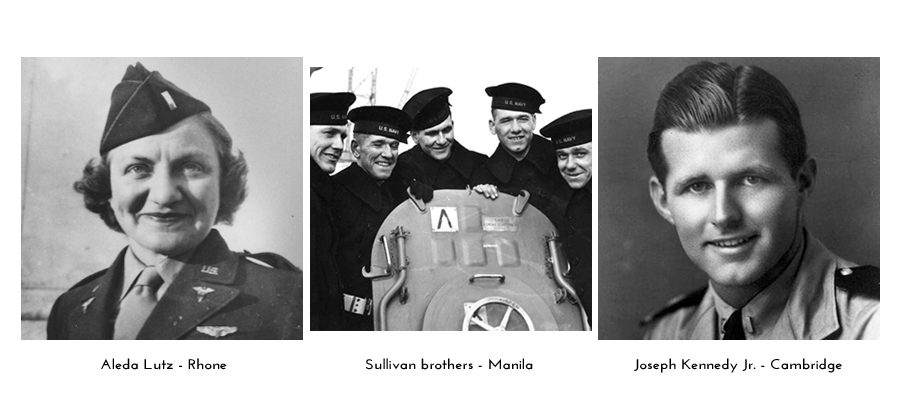

At Cambridge American Cemetery, 30 acres in size, 3,811 heroes rest peacefully—most of these fallen “Yanks” fought the air war over European skies, while a number died in the Battle of the Atlantic and during the invasions of North Africa and France. Additionally, there are the names of 5,127 missing comrades engraved on extensive wall tablets to be honored, whose remains were never recovered or identified. Of these names you’ll find Alton G. Miller, famously Glenn Miller (pictured), the big-band leader hailed for such mega hits as “In the Mood,” “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” and the dreamy “Moonlight Serenade,” who was never found after his plane went down over the English Channel on his way to entertain the troops in France, December 1944. Another name is that of Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. (pictured in the slider at the top of the page), a handsome bomber pilot and the elder brother of the 35th U.S. President. (It was “Joe” who the family planned to be POTUS.)

At Cambridge American Cemetery, 30 acres in size, 3,811 heroes rest peacefully—most of these fallen “Yanks” fought the air war over European skies, while a number died in the Battle of the Atlantic and during the invasions of North Africa and France. Additionally, there are the names of 5,127 missing comrades engraved on extensive wall tablets to be honored, whose remains were never recovered or identified. Of these names you’ll find Alton G. Miller, famously Glenn Miller (pictured), the big-band leader hailed for such mega hits as “In the Mood,” “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” and the dreamy “Moonlight Serenade,” who was never found after his plane went down over the English Channel on his way to entertain the troops in France, December 1944. Another name is that of Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. (pictured in the slider at the top of the page), a handsome bomber pilot and the elder brother of the 35th U.S. President. (It was “Joe” who the family planned to be POTUS.)

Watching over the 472-foot-long Wall of the Missing and Court of Honor are four sculpted members of the U.S. armed forces (soldier, sailor, airman, and coast guardsman) on perpetual guard duty. The former cemetery superintendent, Michael W. Green, said it best when he said: “Our mission is to never forget what they did for us. It is the visitor who validates their sacrifice.”

Cambridge American Cemetery—consecrated on July 16, 1956, on land donated by the University of Cambridge—is the only permanent American World War II military cemetery in Britain. The memorial building is made from Portland Stone, the same material used to build St. Paul’s Cathedral as well as many other significant structures in London. Each of the memorial building’s five central pylons represent one of the years the United States fought in World War II (1941-45)—above is the inscription “GRANT UNTO THEM O LORD ETERNAL REST.”

Among the fallen represented at Cambridge American Cemetery are those from Operation Tiger, a large-scale D-Day training exercise off the south coast of England (April 27-28, 1944) that went horribly wrong when a flotilla of German E-boats, under the cover of a moonless night, attacked the defenseless U.S. naval convoy killing some 700 soldiers and sailors. Because the operation was shrouded in pre-invasion secrecy, the German attack wasn’t declassified until months after D-Day, when the casualties were quietly mixed in with those of the Normandy campaign to avoid a public outcry as to why a massive training exercise involving some 23,000 men was not adequately protected against an enemy attack.

The sizeable 4,000-square-foot visitor’s center at Cambridge American Cemetery is comprehensive, a museum unto itself — allow at least 90 minutes for a visit to both the cemetery and visitor’s center. WWII buffs can easily spend half a day here.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located about 3 miles west of the university city of Cambridge, off hwy A1303, 60 miles north of London. Drivers, from London take the M11 motorway north and exit at No. 13 (A1303); turn left direction Bedford (A428) and the cemetery is a short distance ahead on the right. Railers, you can reach Cambridge via train from London (Liverpool Street or King’s Cross stations) in about 60 min, then taxi from outside the station.

![]()

Brett hand-drew the following map to give you a better idea of where the cemeteries are located within France and England.

FRANCE

10) Normandy American Cemetery

Normandy American Cemetery is the largest in size and by far the most visited with more than 1 million of

us coming to pay our respects annuallyAt Normandy American Cemetery, 172 acres in size, 9,387 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom died on Omaha and Utah beaches and during the ensuing operations to liberate France. Of all the ABMC memorial parks, Normandy American Cemetery is the largest and by far the most visited with more than 1 million of us coming to pay our respects annually. This hallowed ground, framed by bristly pine trees home to families of singing birds, is majestically perched above wind-swept Omaha Beach overlooking the English Channel. It was from this turbulent waterway more than 80 years ago that one of the greatest invasion forces in the history of the world materialized, dubbed Operation Overlord and known to all as D-Day.

The Day of Days: Early Tuesday morning, June 6, 1944, the Germans woke in their coastal defenses to a truly awesome sight: an armada of warships – cruisers, destroyers, escorts, troop transports, gun boats, minesweepers, assault and landing craft – some 7,000 in all, delivering 150,000 men, filled the twilight horizon as far as the eye could see. Sea sick and frightened, the men were brought ashore by specially designed landing craft known as Higgins boats, each transporting 36 soldiers. The landing craft lowered their iron ramps onto Omaha Beach at 6:30 a.m. and the first wave of troops rushed into a killing zone. GIs had to dash across some 200 yards of exposed beach under merciless enemy fire while sidestepping mines, steel obstacles, tank traps, barbed wire, and ultimately concrete bunkers housing scores of German soldiers armed with machine guns, grenades and howitzers on the very bluff where the cemetery now stands. Within the first two hours of combat, 2,400 Americans were dead—thus began the longest day on bloody Omaha Beach!

In all, some 29,000 U.S. servicemen fell during the 8-week Normandy campaign. They came from all walks of life, from every state in the union. They rose from the sea and dropped from the sky like angelic crusaders to rescue a continent. They fought for freedom, for America, for France, for their buddy, for it was their duty. They succeeded, and made no fuss about it.

Thousands of everyday heroes paid the ultimate price; the immense array of white-marbled crosses standing above the soft green lawn is a testament to their valor and selfless actions. They got a one-way ticket to Europe with no chance to ever embrace their mother or daughter again or savor the radiant beauty of a sunset.

Come here, I implore you, bring your children, it is a history lesson—a lesson you will never forget. When you arrive, you’ll learn the soldiers died liberating the field on which you stand, they died for the people of France, they died for you, they died for a cause, and they lie before you; a reminder that freedom comes at a tremendous cost. If they could speak, they would tell you to make the most of it—make the most of your life!

The Cemetery: A mere two days after the Normandy landings, members of the Graves Registration Service began burying the dead on the terrain that is today Normandy American Cemetery—thus establishing the first American World War II burial ground on European soil. Among the 9,387 patriots interred here, three are Medal of Honor recipients, and four burials include women; there are 38 sets of brothers who rest side by side, and in one case father and son: Col. Ollie Reed and 1st Lt. Ollie Reed Jr. (plot E, row 20, graves 19 & 20). Medal of Honor recipient and son of former president “Teddy” Roosevelt, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. is buried next to his brother Quentin (plot D, row 28, grave 45). And the brothers who inspired the movie “Saving Private Ryan,” Preston and Robert Niland are also among the deceased (plot F, row 15, graves 11 & 12). Additionally, there are 307 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified, their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

Men like the Niland brothers, and the Reeds, and the more than 9,000 other valiant warriors who rest on this gentle field, came from an era when charity and altruism were as common as root beer and vanilla ice cream at the soda shop. It is their can-do character, men of integrity, who grew up knowing the hardships of the Great Depression and then went on to fight a world war. Men like these borne from a high-caliber mold, who forever rest beneath white crosses in small fields liberated by American blood across Europe and Africa and Asia, are what moved journalist Tom Brokaw to coin the term, “The Greatest Generation.”

In the center of the cemetery is the memorial chapel, a rotunda made of Vaurion limestone. Chiseled into its interior north wall are poignant words that (I believe) capture the essence of the ABMC and duly commemorate our fallen heroes: “THINK NOT ONLY UPON THEIR PASSING, REMEMBER THE GLORY OF THEIR SPIRIT.”

From the D514 coastal road, the cemetery can be entered via a 1 kilometer tree-lined avenue leading to the parking area and visitor’s center. West of the parking lot, imbedded in the lawn opposite the administration building and covered by a pink granite slab, is a sealed time capsule containing news reports of the Normandy landings. It is dedicated to Dwight D. Eisenhower and is to be opened on the 100th anniversary of D-Day: June 6, 2044. From the parking lot, paths lead to both the *visitor’s center and the crescent-shaped memorial, which features giant wall maps outlining the Normandy operations and the Allied advance across Western Europe. The centerpiece of the memorial is a 22-foot-tall bronze statue cast in Milan, Italy, representing the “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.” Behind it are beds of roses, elm trees, and golden cypress in the Garden of the Missing, commemorating the 1,557 comrades who gave their lives for freedom and sleep in unknown graves (their names are inscribed on the extensive wall enclosing the garden). From the bronze statue an unforgettable view of the cemetery can be observed, beginning with the reflecting pool flanked by American flags that flap before a sea of white-marbled headstones. The everpresence of landscape gardeners assure that the grounds are kept in absolute pristine condition deserving of the supreme sacrifice made by the soldiers who rest here. (But please note that the aforesaid care and dedication is the same for all ABMC memorial parks.)

From the memorial a walkway leads to a viewpoint overlooking Omaha Beach, where an orientation table outlines the D-Day landings and a path descends to the shoreline (though the path is no longer open to the public due to security concerns). From this perch, hellish visions of the opening scenes of the movie “Saving Private Ryan” will no doubt run through your head as you gaze upon the beach below, giving you a remarkable insight into what a human can endure when pushed to the limits under unfathomable circumstances.

*Note: Allow at least two hours to visit Normandy American Cemetery. Start at the visitor’s center, browse its whopping 30,000 square feet, one-third of which is dedicated to exhibition space, e.g. photos, films, interactive displays, and personal stories from combat soldiers who were there. Join a free cemetery tour; ask staff for schedule.

To get there; Normandy American Cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 and till 18:00 April 15 thru Sept 15, except closed December 25 and January 1) is located above the beach at Colleville-sur-Mer, 45 km northwest of Caen and 275 km from Paris. Drivers, from Paris take the A13 tollway (péage, blue signs) to Caen then (as you approach the city) connect onto the northern periphery (Périphérique Nord) skirting Caen. Follow green signs direction Cherbourg. After passing Bayeux (N13) exit at the D30A heading direction (Omaha Beach) Colleville-sur-Mer (D517), then after a few kilometers turn right on the D514 to the cemetery, Cimetière Militaire Américain; (if you were to continue straight on the D517 it would lead you down to Omaha Beach). Railers, there is a fairly regular train service between Paris (Gare St.-Lazare) and Bayeux (2.5hr), where cabs are available (about 17 km to cemetery).

Join our D-Day Beaches & Beyond tour and visit Normandy American Cemetery with Brett Harriman

There is so much to see in this part of Normandy, for example a number of wowing museums and seemingly on every corner is a monument remembering the liberating unit or the name of a soldier who fell. • Don’t miss the beaches, especially Omaha, Utah and Gold. • The bunkers at Pointe du Hoc (13 km west of Normandy American Cemetery); this bluff also belongs to the ABMC. Ronald Reagan gave his D-Day speech here on June 6, 1984, directly in front of the spear-shaped monument. • St.-Mére-Eglise was the first town to be captured (notice the paratrooper hanging from the church belfry, whom Red Buttons played in the movie “The Longest Day”). • The Pegasus Bridge was the scene of the first battle of D-Day; the bridge was renamed “Pegasus” after the British gliderborne units that secured it. • At Arromanches, Gold beach, you’ll find the “Mulberry” harbors, or artificial ports. • What’s more, about 150 km southwest of Normandy American Cemetery is the island abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel and Brittany American Cemetery (see next entry).

Commonwealth and other cemeteries in Normandy: Bayeux War Cemetery (Bayeux) is the largest Commonwealth cemetery of the Second World War in France, where 4,144 of its brave sons rest peacefully. Canada has two cemeteries: Reviers (Beny-sur-Mer) and Cintheaux—in each more than 2,000 heroes rest peacefully. Additionally, La Cambe Cemetery, Germany’s largest in the region, is near Omaha Beach and has more than 21,000 soldiers buried.

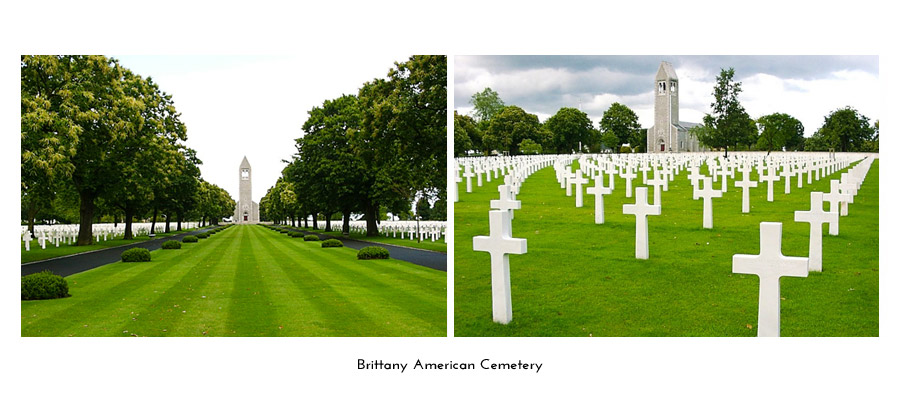

11) Brittany American Cemetery

...grateful locals “adopt individual graves and visit frequently to pay their respects.”At Brittany American Cemetery, 28 acres in size, 4,409 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom fought in the Brittany and Normandy campaigns. Engraved below the flag posts, fronting the burial ground, are the names of an additional 500 missing comrades to be honored. At this serene memorial park positioned at the point where U.S. forces busted through the hedgerow country of Normandy and into the plains of Brittany during the Third Army’s drive to liberate northwest France, grateful locals “adopt individual graves and visit frequently to pay their respects.” Absorb the tranquil scene by climbing the chapel’s 98 steps to reach sensational views of the cemetery and Brittany’s pastoral plains as well as (on clear days) to the salty sea punctuated by the island monastery Mont-St.-Michel, 25 km to the northwest. Among the thousands of patriots interred at Brittany American Cemetery, two are Medal of Honor recipients, and 21 sets of brothers rest side by side. Additionally, 97 headstones mark the graves of servicemen whose remains could not be identified, known but to God.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located 2 km southeast of the village of St. James, 20 km south of Avranches, 22 km north of Fougéres, 150 km south of Normandy Cemetery, and 340 km west of Paris. Drivers, from Paris take the A13 tollway (péage, blue signs) to Caen then (as you approach the city) connect onto the southern periphery (Périphérique Sud) skirting Caen (direction Rennes). On the southwest side of town turn off the periphery (exit No. 9) continuing in the direction of Rennes (blue sign), which will wind you around and onto the A84. Roughly 15 km south of Avranches exit at No. 32 and follow signs into St. James (D30). In the middle of St. James it gets a tad tricky: at the point where you cannot go straight anymore and must choose left or right, go right direction Hamelin (D998) then just ahead make the second left (down narrow lane) where you start picking up signs to the cemetery. Drivers, from Bayeux (Normandy), drive the country route D6 south to Villers-Bocage and connect onto the A84 expressway direction Rennes (then follow directions above, “Roughly 15 km south of Avranches exit at No. 32…”). Drivers, from St.-Mére-Eglise (Normandy) head south to Carentan and drive the country route N174 via Saint-Lô to the A84 expressway direction Rennes (then follow directions above, “Roughly 15 km south of Avranches exit at No. 32…”).

![]()

If you haven’t already, watch this five-minute ABMC production called Fields of Honor

FRANCE

12) Lorraine American Cemetery

Here lies the largest number of American dead from World War II in EuropeAt Lorraine American Cemetery, 113 acres in size, 10,489 heroes rest peacefully—most are from the Seventh Army, who died while battling desperate German forces backed up against the western borders of the Reich, from the fortifications of Metz to the Siegfried Line and from the Rhine River to the Mosel. At Lorraine Cemetery lies the largest number of American dead from World War II in Europe—three of these are full-bird colonels, 11 women (6 Red Cross and 5 Army Corps), four Medal of Honor recipients (whose gravestones are inscribed in gold lettering), and 30 sets of brothers who rest side by side, including one pair of twins: Harold and Howard Rothgeb (plot D, row 45, graves 12 & 13). Also buried here is Charley Havlat from Nebraska (plot C, row 5, grave 75), who died on May 7, 1945 and is generally believed to be the last U.S. soldier killed in combat in Europe during World War II.

Positioned on a knoll and towering over the vast symmetrical rows of white-marble headstones is the commanding presence of the 67-foot-high memorial chapel made of Euville limestone from this picturesque region of Lorraine in northeast France. On its face is a large 26-foot carving of St. Avold, a Roman soldier martyred circa 303 A.D. for his Christian beliefs, seen here with outwardly extended hands blessing the war dead. Above his head is an angel blowing a trumpet. Suspended upon the far interior wall of the chapel are five sculpted figures representing the perpetual struggle for freedom—the youthful and dominating central figure symbolizes future generations while his four companions are historical icons (from l. to r. [King] David, Emperor Constantine, King Arthur and George Washington), who in centuries past have battled for equality and independence. Beneath them are these epic words: “OUR FELLOW COUNTRYMEN; ENDURING ALL AND GIVING ALL; THAT MANKIND MIGHT LIVE IN FREEDOM AND IN PEACE; THEY JOIN THAT GLORIOUS BAND OF HEROES, WHO HAVE GONE BEFORE.” Outside, flanking the memorial tower and facing the immeasurable array of crosses, are the engraved names of 444 comrades on the Wall of the Missing whose remains were never recovered. From here a broad flight of steps descends to the crosses landscaped in nine plots.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located just off the A4 tollway next to the town of Saint-Avold, 5 km from the German border, 27 km west of Saarbrücken (Germany), 45 km east of Metz, 115 km northwest of Strasbourg, 360 km east of Paris, and about an hour’s drive from Luxembourg American Cemetery (No. 17). Drivers, from Paris take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) east all the way to the cemetery, following signs to Metz then Saarbrücken and exit at No. 39, Saint-Avold. Drive towards Saint-Avold and the cemetery is just ahead on the left. Note: In this part of France you’re in the heart of the Maginot Line. Built in the 1930s and named after its creator, the French war minister André Maginot, the Maginot Line was a defensive chain of bunkers that extended along the French border, from the province of Alsace to Belgium, designed to prevent another bloody, WWI-style engagement with Germany. If interested in visiting one of these fortresses, ask cemetery staff to point you the way. Drivers, from Strasbourg take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) north following signs to Metz/Paris and exit at No. 39, Saint-Avold. Drive towards Saint-Avold and the cemetery is just ahead on the left. Railers, Saint-Avold station is about 5 km from the cemetery but there are no taxis available. However, if you are a family member of one of the interred soldiers, call the cemetery in advance +33-(0)3/8792-0732 and let them know when your train is scheduled to arrive; if a staff member is available he or she will pick you up.

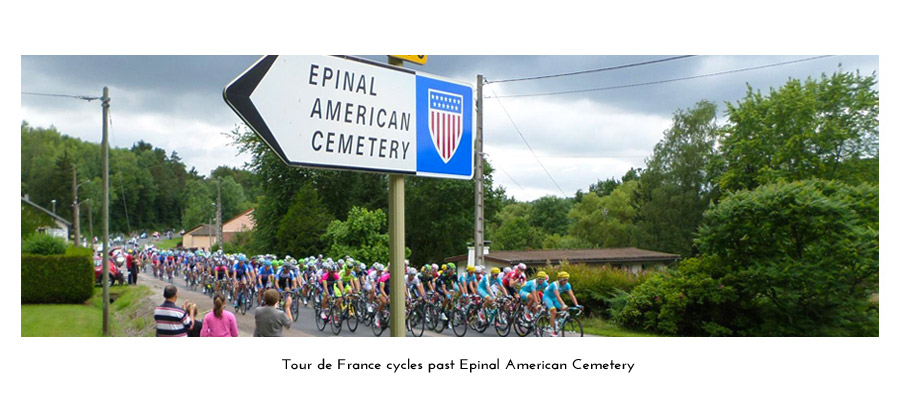

13) Epinal American Cemetery

The journey of the Unknown Soldier began hereAt Epinal American Cemetery, 48 acres in size, 5,255 heroes rest peacefully, representing 42% of all original U.S. burials in the region—most of whom lost their lives while fighting in campaigns across France and into Germany. The cemetery site—liberated on September 21, 1944, by the 45th I.D. (Seventh Army)—is quaintly nestled upon a wooded plateau gently running into the Mosel River. Among the patriots interred here are four Medal of Honor recipients (one of them, Sergeant Gus J. Kefurt from Ohio, plot A, row 29, grave 37, was killed on Christmas day, 1944), and 14 sets of brothers who rest side by side. In addition, buried here are members of the highly revered 442nd Infantry Regiment comprised mainly of Nisei, or Japanese-Americans, whose uncommon valor in the face of the enemy made them as a whole the most decorated unit (of its size and length of service) in the U.S. military during World War II (all while many of its soldiers’ families were deemed enemy aliens on the homefront and held in internment camps after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor). Engraved on the walls made of Rocheret limestone framing the Court of Honor are the names of an additional 424 missing comrades to be honored. An inscription reads: “THIS IS THEIR MEMORIAL, THE WHOLE EARTH THEIR SEPULCHER.”

On the morning of May 12, 1958, 13 caskets draped with American flags were placed side by side under a canopy at the north end of Epinal American Cemetery. Each casket contained the remains of one unknown serviceman from each of the permanent World War II ABMC cemeteries established in the European theater (including North Africa American Cemetery). Once the caskets were in place, the honor guard stood at attention as the dignitaries and commanding general arrived. General Edward J. O’Neill slowly paced alongside each of the 13 flag-draped coffins, turned and made a second inspection, at which point the general picked up a wreath and proceeded to the fifth casket, placing the wreath upon it. He then stood at attention and saluted as Taps sounded. The sobering ceremony concluded as pallbearers carried the unknown serviceman selected by the general to a waiting hearse. The hearse—under escort—drove to Toul-Rosièrs Air Base, France, where the coffin was flown to Naples, Italy, and loaded aboard the destroyer USS Blandy. The destroyer rendezvoused in the Atlantic with a U.S. naval task force (specifically the USS Canberra) that was transporting two other unknown servicemen, one from the Pacific theater of World War II and the other from the Korean War. Between the two World War II unknowns, from the Pacific and European theaters, a similar selection ceremony was held, this time by Hospitalman 1st Class William R. Charette, then the Navy’s only active-duty Medal of Honor recipient, to determine which World War II unknown would represent both theaters of the war. The final selection was made and the task force landed in Washington, D.C., where on Memorial Day 1958, the World War II and Korean War unknowns joined the Unknown Soldier from World War I at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is situated 7 km south of Epinal on road D157, neighboring the village of Dinoze-Quequement, 75 km south of Nancy and 375 km east of Paris. Drivers, from Paris (roughly 5 hours), take the A4 tollway (péage, blue signs) east to Metz then connect onto the A31 south to Nancy. From Nancy continue south on the A33 to the A330 then N57 to Epinal; bypass Epinal and, immediately after crossing the Mosel River, exit at Arches-Dinozé then turn right on the D157 to the cemetery 4 km ahead on the left. Drivers, from Colmar it’s a long but scenic 100 km on a windy road through the lower Vosges mountains. Take the D417 west out of Colmar through the lakeside town of Gérardmer and turn right up the hill (D11) direction Epinal. On the west side of Docelles turn right to Cheniménil (D159B); at the crossroads in town turn right to Jarménil and some 5 km farther cross the Mosel River and jump onto the N57 hwy direction Epinal. Get off at the next exit, Arches-Dinoze, then turn right on the D157 to the cemetery 4 km ahead on the left.

14) Rhone American Cemetery

One heroic woman, Army Air Corps flight nurse Aleda Lutz, flew an astounding 196 missions to help evacuate

and medically assist more than 3,500 servicemen before losing her life At Rhone American Cemetery, 12 acres in size, 860 heroes rest peacefully with another 294 comrades to be honored on the Wall of the Missing—many of whom lost their lives while fighting with General Patch’s Seventh Army for the liberation of southern France in August 1944. That same month on the 19th the burial ground was established, a mere four days after the Allied coastal invasion (Operation Dragoon) that struck due south on the French Riviera (Côte d’Azur) to assist the Normandy operations. Of the hundreds of patriots interred here, there are two sets of brothers who rest side by side, the only U.S. Marine from World War II buried in France (SSG Charles Perry died while on a secret mission behind enemy lines to assist and train the French Resistance), and one woman (pictured in the slider at the top of the page): 1st Lt. Aleda Lutz from Michigan (plot D, row 8, grave 19), who flew an astounding 196 missions as an Army Air Corps flight nurse helping to evacuate and medically assist more than 3,500 servicemen. It was upon one of these missions from the front that the C-47 she was flying in crashed, killing all aboard (Nov. 1, 1944). For her dedicated service and altruistic duty to her country and comrades, Lutz received the Air Medal four times and posthumously she became the second woman to ever be awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC); the first was Amelia Earhart! In her honor, the VA Medical Center in Saginaw, MI, bears her name, as well as the Army hospital ship USAHS Aleda E. Lutz.

Now located on John Kennedy Boulevard, this eloquent memorial park is situated 25 km inland from the sun-soaked Riviera and neatly blends with everyday French living; nearby are schools and playgrounds and rustic hillside villas overlook the rows of crosses framed by thriving columns of Italian cypress and hackberry (Celtis Australis) trees. The landscaped gardens feature manicured lawns dotted with age-old olive trees (characteristic of the Mediterranean) centered around a circular pool while vibrant seasonal plant beds stoke the evergreen shrubs (such as the oleander and crape myrtle) that maintain their depth all year. At the head of the cemetery an enormous Angel of Peace carved onto the memorial tower made of white limestone oversees the war dead with prayer. Beneath the angel an inscription reads: “WE WHO LIE HERE DIED THAT FUTURE GENERATIONS MIGHT LIVE IN PEACE.” Inside the tower is the memorial chapel accentuated by a stunning array of mosaics recreating the Great Seal of the United States and golden stars seated within a baby-blue sky.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is situated within the city of Draguignan, 45 km north of St.-Tropez and 65 km west of Cannes. Note: The visitors’ building is located immediately right of the entry gate as you approach. Drivers, from Cannes take the A8 tollway (péage, blue signs) west direction Marseille and exit at No. 36 to Draguignan (N555 – D1555). When you reach Draguignan follow signs through town towards the Centre. Just after the small traffic-lighted intersection (with petite fountain in center) turn right following the cemetery sign onto the residential street (Boulevard Ferdinand Buisson) straight to the memorial park at the end (go right at T to entrance on left).

![]()

ITALY

15) Florence American Cemetery

Idyllically landscaped on a forested slope along the Greve River, Florence Cemetery is a must-see for any

American visiting the province of TuscanyAt Florence American Cemetery, 70 acres in size, 4,402 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom lost their lives in combat liberating cities and townships from Rome to the Alps, from mid-1944 until the surrender of the German army in Italy, May 2, 1945. Idyllically landscaped on a forested slope along the Greve River, Florence American Cemetery is a must-see for any American visiting the province of Tuscany. Sign the guest registry at the visitors’ building, pick up an info sheet, march across the river via the bridge and onto the field of honor. Gaze the seemingly endless rows of white crosses and contemplate the cost of freedom. The magnitude of death here is astounding! We are so minuscule among these giants, whose number include three Medal of Honor recipients (including bomber pilot Lt. Col. Addison E. Baker memorialized on the Wall of the Missing), four women (two of which were American Red Cross), five sets of brothers who rest side by side, and an additional 1,409 names of missing comrades engraved on Baveno granite panels along the Memorial Walk. One inscription reads: “THEIR BODIES ARE BURIED IN PEACE, THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE.”

At the height of the burial ground is the memorial building and chapel, fronted by a tall stone obelisk capped with a carved figure representing the “spirit of peace” overlooking the fallen. Step through the chapel’s bronze doors and onto an immaculate floor made from Verde Serpentino marble, take a pew crafted from rich walnut wood, note the polished altar hewn from black Belgian marble, and behind it the glorious wall mosaic depicting Remembrance upon a cloud holding the lilies of Resurrection above a field of headstones awaking to the warmth of spring. The Memorial Walk, shaded by plane trees and lined by the Tablets of the Missing, connects the north atrium featuring resplendent wall mosaics embellished by various types of multihued marble and the local “intarsia” art form to uniquely illustrate American military operations in Northern Italy from mid-1944 till the end of the war (May 1945).

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is situated on the Via Cassia (route SR2) some 10 km south of Florence and 275 km north of Rome. Railers, pick up a “Sita” bus near the Florence main train station (SMN) to the stop (Cimitero Americani) located directly outside the cemetery entrance. Drivers from downtown Florence, head south direction Siena and after crossing the autostrada (A1) you’ll reach a large traffic circle; drive straight through the circle and follow signs to Tavarnuzze (SR2)—the cemetery is about 2 km beyond the town. Drivers from greater Florence, exit the A1 autostrada at Firenze Impruneta. Drive straight through the traffic circle and follow signs to Tavarnuzze (SR2)—the cemetery is about 2 km beyond the town. Drivers from Rome—your best bet is to visit the cemetery before arriving in Florence—take the A1 autostrada north direction Florence (Firenze) all the way and exit at Firenze Impruneta. Drive straight through the traffic circle and follow signs to Tavarnuzze (SR2)—the cemetery is about 2 km beyond the town.

![]()

Harriman hand-drew the following map to give you a better idea of where the cemeteries are located within Italy.

16) Sicily-Rome American Cemetery

Most warriors buried here lost their lives in combat during campaigns to liberate southern Italy: Sicily,

Salerno, Anzio, Rome...At Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, 77 acres in size, 7,861 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom lost their lives in combat during *campaigns (explained in the next paragraph) to liberate southern Italy, for example Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Rome. Among these warriors are two Medal of Honor recipients, 17 women, and 23 sets of brothers who rest side by side. Engraved on the walls within the chapel are the names of an additional 3,095 missing comrades to be honored. An inscription reads: “NOBLY THEY ENDED, HIGH THEIR DESTINATION.” At the head of the cemetery, two 80-foot-tall flagpoles flank the neoclassic-style memorial building that includes the chapel and a connecting colonnade predominantly shaped from Roman travertine quarried near Tivoli (a few miles east of Rome). Within the colonnade the exceptional “Brothers-in-Arms” sculpture cast in bronze captures the spirit of the cemetery, symbolizing the solidarity between soldier and sailor. Step inside the chapel and behold a floor made from Rosso Levanto marble quarried near Genoa, pews fashioned from rich walnut wood, and walls made of white Carrara marble bearing the names of the missing. The dramatic ceiling design represents the constellations of the zodiac. The planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn occupy the same positions they did at 0200 January 22, 1944, when the first U.S. troops landed on the nearby beaches of Anzio. Opposite, in the map room, large wall frescos combined with marble mosaics brilliantly illustrate American military operations in Sicily and Italy from 1943-45.

*Soon after the defeat of Rommel’s Afrika Korps from Egypt to Tunisia, British and American forces invaded Sicily on July 10, 1943. In just 39 days the Allied generals, Patton and Montgomery, raced their hard-hammering troops around Sicily and expelled the Germans from the island. It was an astounding victory that opened the door to the European continent while also triggering the dissolution of the Italian government’s partnership with Nazi Germany. The next step of the plan dared to gain a foothold on the mainland of Italy itself. This was achieved on September 9, 1943, when troops of the U.S. Fifth Army made an amphibious landing at Salerno and secured the beachhead. The U.S. landing party subsequently battled their way inland to rendezvous with British troops who had since crossed the Straights of Messina. The British and Americans made steady progress, advancing north and liberating communities from Naples to Foggia. Alas, the Allied advance got bogged down in the winter around the heavily defended area of Cassino, half way to Rome. The Germans, under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, were dug in along the so-called Gustav Line, which was firmly anchored on the Garigliano and Rapido rivers as well as the heights of Monte Cassino. Against unwavering opposition, the Allies had but one choice: to outflank the Nazis by initiating a second waterborne invasion, codenamed “Shingle.” Because the Germans had relocated most of their reserves from the coastal areas to the Gustav Line, the beaches of Anzio were lightly defended. At 0200 January 22, 1944, U.S. VI Corps landed at Anzio, completely surprising the enemy. However, this was short lived. German units were quick to respond with reinforcements from northern Italy, France and Yugoslavia, promptly halting the Allied offensive. Hitler’s forces fought tenaciously, making the Allies pay dearly for every meter of ground gained. It took another four bloody months for British and American troops to advance just 65 km to reach the Italian capital, and on June 4, 1944, Rome was liberated[!] (but two days later Allied armies invaded Normandy and the triumph of Rome was sadly relegated to the back pages of history).

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00, till 18:00 April thru September, except closed December 25 and January 1) is situated in the coastal town of Nettuno, which is just a few km east of Anzio and 60 km south of Rome (via route Via Pontina). Drivers, from Rome connect onto the Via Pontina (SS148) heading south direction Pomezia then some 8 km beyond the town of Aprilia exit the highway at Nettuno-Velletri. Turn right to Nettuno and follow this road straight some 9 km to the cemetery (on right, park in front of gate). Railers, catch the regularly scheduled train from Rome to Nettuno (then catch a cab or walk 10 min along Via Santa Maria to cemetery).

![]()

LUXEMBOURG

17) At Luxembourg American Cemetery

Medal of Honor recipient Sgt. Day Turner killed 11 enemy soldiers before taking 25 more prisoner At Luxembourg American Cemetery, 50 acres in size, 5,076 heroes rest peacefully, representing 39% of all original U.S. burials in the region—most of whom fought with Patton’s Third Army in the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge) and eastward to the Rhine. Among these veterans every state in the union is represented, two are Medal of Honor recipients (Pvt. William McGee—his grave is pictured in the slider at the top of the page—and Sgt. Day Turner who killed 11 enemy soldiers before taking 25 more prisoner), 22 sets of brothers rest side by side, and one burial is that of a beautiful Army nurse 2nd Lt. Nancy Leo (pictured) from Maryland (plot H, row 9, grave 71), who sadly died in a jeep accident one month before her 24th birthday. Additionally, there are 101 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified, their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

At Luxembourg American Cemetery, 50 acres in size, 5,076 heroes rest peacefully, representing 39% of all original U.S. burials in the region—most of whom fought with Patton’s Third Army in the Ardennes (Battle of the Bulge) and eastward to the Rhine. Among these veterans every state in the union is represented, two are Medal of Honor recipients (Pvt. William McGee—his grave is pictured in the slider at the top of the page—and Sgt. Day Turner who killed 11 enemy soldiers before taking 25 more prisoner), 22 sets of brothers rest side by side, and one burial is that of a beautiful Army nurse 2nd Lt. Nancy Leo (pictured) from Maryland (plot H, row 9, grave 71), who sadly died in a jeep accident one month before her 24th birthday. Additionally, there are 101 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified, their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

Luxembourg American Cemetery, an immaculate park in a convivial country, was first established as a temporary burial ground on December 29, 1944, by the U.S. Third Army during the fierce winter engagement famously known as the Battle of the Bulge. The following year the cemetery became permanent and today some 80,000 visitors come here annually to pay their respects. About half of these, believe it or not, are foreigners. The Chinese, especially, are big fans of General Patton, who is buried here. (They admire his bravado.)

Enter the memorial park through its decorative wrought-iron gate supported by two stone pillars, each surmounted by a gilded bronze eagle and embossed with a cluster of stars representing the original 13 states. Adorned by thriving Virginia Creeper and resembling a country-style cottage, the visitors’ building is first on the left (and toilets are on the right behind the hedgerow). Beyond the visitors’ building is the chapel: a 50-foot tall yet slender tower made of Valore stone from the Jura mountain region of central France that chimes hourly and Taps daily at 16:45. On its face is a 23-foot “angel of peace,” carved out of Swedish orchid-red granite during a four-week period by an Italian trio of sculptors, overlooking the arcing rows of white-marbled crosses. Beneath the angel and above the chapel entrance is the following inscription in gold lettering: “HERE IS ENSHRINED THE MEMORY OF VALOR AND SACRIFICE.” Flanking the chapel are two giant stone pylons, on which bear the names of 371 missing comrades to be honored (note that nine of these have since been recovered) as well as large-scale battle maps illustrating American military operations in the region and the whole of Western Europe. Between the pylons, emblazoned onto the granite paving in bronze lettering, is a passage by Dwight D. Eisenhower: “ALL WHO SHALL HEREAFTER LIVE IN FREEDOM WILL BE HERE REMINDED THAT TO THESE MEN AND THEIR COMRADES WE OWE A DEBT TO BE PAID WITH GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE OF THEIR SACRIFICE AND WITH THE HIGH RESOLVE THAT THE CAUSE FOR WHICH THEY DIED SHALL LIVE ETERNALLY.”

Fittingly, a few meters from Eisenhower’s passage rests George S. Patton (buried here Christmas Eve 1945), the general most revered by Americans, and most feared by Nazis. They had good reason, as the following Patton quote lends credence to his Old Blood and Guts moniker: “We’re not just going to shoot the sons-of-bitches; we’re going to rip out their guts and use them to grease the treads of our tanks!” Patton is buried between the flagpoles, at the head of his troops (pictured in the slider at the top of the page). Interestingly, Nancy Leo is not the only female presence at Luxembourg American Cemetery. According to the book “The Pattons: A Personal History of an American Family,” authored by Robert H. Patton (the general’s grandson), Mrs. (Beatrice) Patton wished to be buried with her husband. This was not allowed, of course, so prior to her death Beatrice elected to be cremated. After her passing, the Pattons’ children traveled to Luxembourg and scattered their mother’s ashes over the general’s grave. (For more on the burial of Patton and the opening of the cemetery, visit the Patton Historical Society founded by author and U.S. Army veteran Charles M Province.)

Either side of the Pattons a pathway gently descends through the field of honor, enriched by a calming fountain featuring a set of bronze dolphins and turtles playing in cascading pools of water. Like all ABMC memorial parks, Luxembourg American Cemetery is kept in pristine condition befitting the memory of U.S. fallen by a team of dedicated landscape gardeners. And I don’t use the term “dedicated” loosely here. André (pictured), a local national, formerly part of the landscaping team for some 30 years, welled my eyes as he recounted the great sacrifices made by American soldiers to defeat the oppressive rule imposed on his country, his parents, and their parents by Hitler’s brutal regime. I don’t recall ever encountering anyone so fervently patriotic about another man’s country. But that is André. He has not forgotten. And then there is Nico Schroeder, a local retiree, who had been stopping by most every day to pay his respects to the U.S. war dead here since he was a teenager, i.e. 1948. Remarkable, indeed, but gratitude comes from the heart and these folks have plenty for the liberators who reside forevermore in Luxembourg. (With great sadness, Nico left us on January 22, 2015. He was 80 years young, born April 15, 1934. Visit Nico’s Web page for more on his life, Luxembourg American Cemetery, including umpteen photos of ceremonial events, VIPs and returning vets.)

Either side of the Pattons a pathway gently descends through the field of honor, enriched by a calming fountain featuring a set of bronze dolphins and turtles playing in cascading pools of water. Like all ABMC memorial parks, Luxembourg American Cemetery is kept in pristine condition befitting the memory of U.S. fallen by a team of dedicated landscape gardeners. And I don’t use the term “dedicated” loosely here. André (pictured), a local national, formerly part of the landscaping team for some 30 years, welled my eyes as he recounted the great sacrifices made by American soldiers to defeat the oppressive rule imposed on his country, his parents, and their parents by Hitler’s brutal regime. I don’t recall ever encountering anyone so fervently patriotic about another man’s country. But that is André. He has not forgotten. And then there is Nico Schroeder, a local retiree, who had been stopping by most every day to pay his respects to the U.S. war dead here since he was a teenager, i.e. 1948. Remarkable, indeed, but gratitude comes from the heart and these folks have plenty for the liberators who reside forevermore in Luxembourg. (With great sadness, Nico left us on January 22, 2015. He was 80 years young, born April 15, 1934. Visit Nico’s Web page for more on his life, Luxembourg American Cemetery, including umpteen photos of ceremonial events, VIPs and returning vets.)

Special “thanks” to Erwin Franzen, a local national and long-time ABMC employee at Luxembourg (now retired) who dutifully administered the visitor’s building, for providing me with much of the information to complete this entry, including the picture sheet of original burials on this page under Burial. Most every year I stop by Luxembourg mid-October, and every time I could count on Erwin to enlighten me with indigenous histories and cemetery memoirs. It is faithful people like him, and André, and Nico, among countless others, who care for our war dead and make Luxembourg American Cemetery a must-visit destination in this benevolent corner of Europe.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located in the suburb of Hamm, 5 km east of downtown Luxembourg City and equally 5 km from the airport. Railers, from Luxembourg City’s main train station, either catch a cab to the cemetery (40€-50€) or take the bus (20-min ride then 20-min walk). Pick up the bus (typically No. 15, departing about every 15 min, direction Rue de Bitbourg) across the street from the station in front of the Mercure Alfa Hotel. Exit the bus at Rue Haute, march uphill, straight through the traffic circle and at the main intersection follow the footpath to the right, over the rail line and through the trees. The trail feeds into a road at the bottom; take this straight up to the cemetery. Drivers, be sure to fill up your tank while in Luxembourg, gas is cheaper in the Grand Duchy (and note that prices are the same from station to station so don’t bother driving around looking for even cheaper gas). Drivers from Brussels to the cemetery is roughly 215 km: take the expressway southeast out of the city and when you reach Luxembourg City continue on the motorway all the way around the capital in the direction of the airport; exit at No. 7 Sandweiler then follow signs to Cimetière Militaires to the cemetery. Drivers from Trier to the cemetery is only a 40-min drive, or 46 km from the Porta Nigra. As you approach Luxembourg City via the autobahn exit at No. 7 Sandweiler and follow signs to Cimetière Militaires to the cemetery. Drivers from scenic route N10, the wine road (Route Du Vin) along the Moselle River (Lux. side), turn at the town of Remich onto the N2 direction Luxembourg (City). Some 16 km up this country road you’ll reach a large traffic circle on the other side of Sandweiler; follow it around and turn off at Cimetière Militaire Américain (small white sign). Down the hill make the first right, then turn immediately right again. Ahead, on the right curve, pull into the cemetery parking lot. Note: After your visit, consider driving over to the nearby German military cemetery (where some 11,000 soldiers are buried, 4,829 of these in a mass grave)—from the U.S. cemetery parking lot follow signs Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof, 1 km. You’ll see a huge difference between the two memorial parks. Notice at the German cemetery each gravestone is marked with four names. Drivers, to Trier from Luxembourg American Cemetery: Exit the cemetery parking lot left and at the main road you want to go left but it’s illegal (because of the heavy traffic), so go right up the hill and drive around the traffic circle and come back down the hill. At the traffic circle ahead exit right following the blue autobahn sign to Trier. The Lux-German border is 30 km from here at Wasserbillig and your last chance to fill up the tank. Take the first exit on the German side for Trier. Drivers, to Ardennes American Cemetery from Luxembourg American Cemetery is roughly 180 km, two hours depending on traffic.

Join our Belgium Beer & Battlefields tour and visit Luxembourg American Cemetery with Harriman

![]()

Harriman hand-drew the following map to give you a better idea of where the cemeteries are located within the Benelux countries.

HOLLAND

18) Netherlands American Cemetery

Landscaped in a rural setting near Germany, this thought-provoking memorial park is the first of its kind

to be allocated for U.S. soldiers who died on German soil as well as the only American military cemetery

in the NetherlandsAt Netherlands American Cemetery, 65 acres in size, 8,301 heroes rest peacefully, representing 43% of all original U.S. burials in the region—most of whom fought with the U.S. First and Ninth armies as well as the 101st and 82nd airborne divisions for the liberation of the Netherlands and during combat operations into Nazi Germany. If you’ve seen the 1977 epic war film “A Bridge Too Far” (portraying the failed Operation Market Garden) starring some of Hollywood’s biggest names—James Caan, Robert Redford, Gene Hackman, Sean Connery, Michael Caine, Anthony Hopkins, Laurence Olivier—then you have a good understanding of the bitter fighting that took place here (Eindhoven, Grave, Nijmegen, Arnhem, Venlo) and why so many American dead lie on these otherwise bucolic flatlands. Among the fallen are six Medal of Honor recipients (one such warrior is PFC Walter Wetzel from Michigan—plot N, row 18, grave 10—who threw himself on two enemy grenades during a German attack to save his buddies), and the tremendous sacrifice of the American family is doubled here in the 40 instances of brothers resting side by side. In addition to the more than 8,000 white-marbled crosses that span 16 massive plots are the engraved names of 1,722 comrades whose remains have not been found or identified and are remembered on the Wall of the Missing in the Court of Honor. Recalling John McCrae’s emotive poem “In Flanders Fields,” the following line on the north wall reads: “TO YOU FROM FAILING HANDS WE THROW THE TORCH; BE YOURS TO HOLD IT HIGH.” (To read the full poem, see Flanders Field American Cemetery [No. 1] on this page.)

Landscaped in a rural setting near Germany, this thought-provoking memorial park is the first of its kind to be allocated for U.S. soldiers who died on German soil as well as the only American military cemetery in the Netherlands. Seen from a distance, the 101-foot-high memorial tower and observation platform made of (English) Portland Stone marks the entrance to the burial ground. Below the tower, visitors move pensively through the Court of Honor along its reflecting pool and flanking panels belonging to the Wall of the Missing. At the pool’s edge stands the poignant statue of a mother grieving for her lost son while beside her three doves signifying peace cast flight. Enter the tower into the memorial chapel through a bronze portal designed as a “tree of life.” Above its entrance are the engraved words: “IN MEMORY OF THE VALOR AND THE SACRIFICES WHICH HALLOW THIS SOIL.” Fittingly, on May 8, 2005, Netherlands American Cemetery was the chosen site of a presidential visit when George W. Bush addressed an audience of dignitaries for the 60th anniversary of V-E Day.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) neighbors the village of Margraten, 9 km east of Maastricht, the Netherlands, and 20 km west of Aachen, Germany. Railers, bus No. 350 departs regularly from Maastricht main train station and stops at the cemetery. From Aachen, catch the bus to Vaals (in the Netherlands) then change to bus 350. Drivers, the memorial park lies on route N278 between the cities of Maastricht and Aachen. If you’re coming from Aachen, cross the border at Vaals and the cemetery entrance is on the left after passing Margraten. Note: Allow extra time to visit Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery (next entry), a 15-20 min drive across the border into Belgium (see staff in the visitors’ building for directions). But in case a staff member is unavailable; from Netherlands American Cemetery exit right towards Aachen and after passing Margraten turn right following signs to Reijmerstok then the border village of De Plank (and into the historical province of Limburg, whose inhabitants are world renown for their pungent cheese). Continue straight and at the crossroads turn left; at the upcoming traffic circle drive direction Welkenraedt and the cemetery is ahead on the left.

Join our Belgium Beer & Battlefields tour and visit Netherlands American Cemetery with Harriman

![]()

BELGIUM

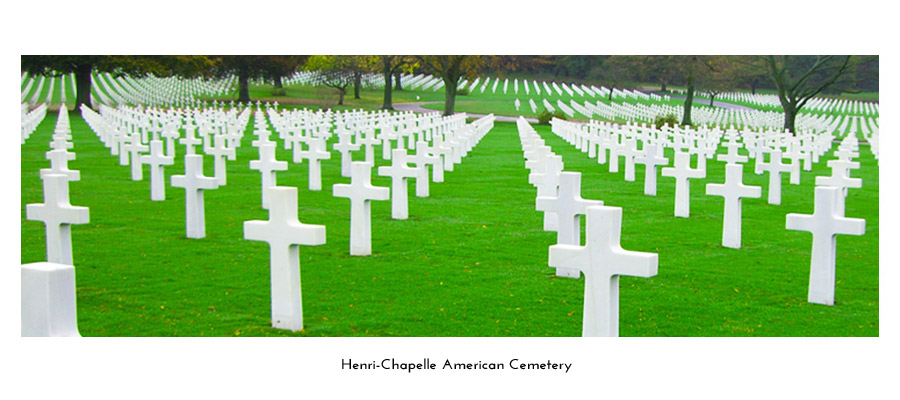

19) Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery

To bid farewell, a ceremony was held and more than 30,000 teary-eyed Belgian citizens lined the roads to express

their eternal gratitude to the brave young Americans who, in the prime of their lives, died to liberate them

from Nazi tyrannyAt Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery, 57 acres in size, 7,992 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom fought in the great Battle of the Bulge as well as in the bloody Hürtgen Forest, through the Low Countries, and the intense battle for Aachen (which became the first major German city to be captured by the Allies).

Idyllically positioned on a pastoral plateau, the cemetery boasts panoramic vistas of the Belgian countryside, formerly a battlefield. Upon arriving, stroll past fragrant beds of roses and into the elongated memorial building that is supported by an arcade of 24 lofty pillars. Within this large open-air colonnade are the visitors’ building and chapel as well as the engraved names of 450 missing Americans to be remembered. From here the terrace invites an elevated view sweeping across a sea of white-marbled crosses meticulously arranged in gentle arcing patterns. Surveying the breathtaking scene is an archangel bestowing a laurel branch upon the fallen for whom he eulogizes to the Lord. Among the thousands of patriots interred here, three are Medal of Honor recipients, 33 sets of brothers rest side by side, in one case three brothers lay side by side, and 22 were POWs massacred by their SS captors near Malmedy. Additionally, there are 94 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified, their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

Two years after the war, the numerous makeshift cemeteries filled with American servicemen that dotted the European landscape were consolidated and painstakingly reshaped into permanent shrines. Wooden crosses were swapped for marble and a farmer’s field was replaced by immaculate turf and a sacred chapel. On July 27, 1947, the first transfer of American war dead repatriated to the U.S. came from this burial ground. To bid farewell, a ceremony was held and more than 30,000 teary-eyed Belgian citizens lined the roads to express their eternal gratitude to the brave young Americans who, in the prime of their lives, died to liberate them from Nazi tyranny. Today, most of these Belgians have since passed but their children and grandchildren have taken their place making regular trips to this pastoral pantheon of heroes.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located 3 km north of the village of Henri-Chapelle, between Liege (29 km), Belgium, and Aachen (16 km), Germany, off the country route N3. Railers, catch a train to Welkenraedt, Belgium, then a cab (8 km) to the cemetery. Either arrange a time with the driver to pick you back up or when you’re ready cemetery staff can call you a cab. Drivers, from either Liege or Aachen connect onto the N3 and in the middle of the village of Henri-Chapelle turn north to the cemetery. Note: Allow extra time to visit Netherlands American Cemetery (above entry), a 15-20 min drive north across the border into Holland (see staff in the visitors’ building for directions). But in case a staff member is unavailable; from Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery exit the parking lot right (north) and at the traffic circle ahead continue straight direction Maastricht; at the upcoming crossroads turn right (N648) to De Plank (followed by Reijmerstok). At the T-junction go left direction Maastricht (N278) and the cemetery entrance is ahead on the left after passing Margraten. Drivers, to Ardennes American Cemetery from Henri-Chapelle is roughly 55 km, 45-60 min depending on traffic.

Join our Belgium Beer & Battlefields tour and visit Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery with Harriman

20) Ardennes American Cemetery

Among the thousands of patriots interred here, every state in the union is representedAt Ardennes American Cemetery, 90 acres in size, 5,321 heroes rest peacefully—two-thirds of whom were airmen fighting the strategic air war over Germany while others fought locally with ground units to counter Hitler’s last daunting offensive in the west: Wacht am Rhein (or famously *Battle of the Bulge). The first burials here (Feb. 1945), however, were the victims of a Nazi V-1 rocket attack that struck the American military hospital in nearby Liège. After the war, the cemetery became a central hub for scientific and medical examiners to positively identify the bodies of unknown American servicemen Europe-wide and beyond, thus a number of the burials are from every major U.S. battle fought in Europe, including some from the Pacific and North Africa. Among the thousands of patriots interred here, every state in the union is represented, three are Medal of Honor recipients (including bomber pilot Capt. Darrell R. Lindsey who sacrificed his life to save his crew is memorialized on the Wall of the Missing), and there are 11 instances in which two brothers rest side by side. There are also three cases in which the bodies of airmen could not be separated and are buried together, their headstones read: “HERE REST IN HONORED GLORY TWO COMRADES IN ARMS.” Additionally, 792 headstones mark the graves of servicemen whose remains could not be identified, known but to God.

Ardennes American Cemetery shed its temporary status in March 1949 when the first caskets were lowered into their permanent positions that as a whole cover four sections forming the likeness of a Greek cross, framed by a forest of trees: beech, ash, oak, linden, and spruce. Fronting this field of honor stands the massive square-shaped memorial building, crafted from (English) Portland limestone. Sculpted on its face is a 17-foot American eagle; adjacent are three figures symbolizing Justice, Liberty and Truth; and in the lower corner are two rows of stars representing the original 13 states. Carved onto the back side of the memorial are the colorful (shoulder) insignias of the army and air force groups that represent the majority of men buried here. Flanking the immense limestone structure are 12 granite slabs (6 either side) bearing the names of an additional 463 missing comrades to be honored. Inside the memorial, huge wall maps made from a mosaic of multihued marble slices brilliantly illustrate U.S. military operations across Europe 1944-45, particularly in the Ardennes. At the far end of the building is the chapel altar for prayer and quiet reflection. Outside, a gently sloping path leads through the field of white-marbled headstones to a flag-poled plaza on the northern boundary of the necropolis with thought-provoking views of our young heroes.

(Continued from the opening paragraph, end of first sentence:) *On December 16, 1944, the approach of Christmas warmed the freezing foxholes that were otherwise home to hundreds of thousands of GIs who wanted nothing more than an early end to Hitler’s war. Following the invasion of Normandy, the Allies swept the Nazis from France and Belgium to the German frontier, where by September ’44 the Allied advance had stalled before the enemy’s last-ditch defense fortifications. The front lines had become stagnant and the Americans dug in for winter. The relative stalemate didn’t last long; GIs counting down to the arrival of Saint Nick woke to the earth-shattering bark of howitzers and the terrifying growl of panzers. Hitler unleashed some 250,000 troops across a 50-mile stretch of the Allied front, smashing through the heavily forested and lightly defended Ardennes region of eastern Belgium and northern Luxembourg. Thus began Hitler’s last great offensive in the west, the Battle of the Bulge.

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located just south of the town of Neuville-en-Condroz in Neupre, 20 km southwest of Liège, Belgium, and 80 km southwest of Aachen, Germany. Railers, from Brussels, Paris or Aachen, take the train to Liège main station then taxi (roughly 45€) to cemetery. Either arrange a time with the driver to pick you back up or when you’re ready cemetery staff can call you a cab. Drivers, from the south side of Liège, take the N63 direction Marche and the road will pass the cemetery entrance (right side). Drivers, to Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery from Ardennes Cemetery is roughly 55 km, 45-60 min depending on traffic.

![]()

TUNISIA

21) North Africa American Cemetery

One selfless warrior buried here is Foy Draper, verification that America gave her finest, graduate of USC and

gold medalist at the 1936 Olympics who set a new world record with sporting legend Jesse Owens in the

4 x 100 meter relayAt North Africa American Cemetery, 27 acres in size, 2,841 heroes rest peacefully, representing 39% of all original U.S. burials in the region—many of whom lost their lives while battling Rommel’s Afrika Korps or (Vichy) French forces closely aligned with Nazi Germany. Most were young American men in the prime of their lives who fought and died as brave patriots to a nation, falling in a land they scarcely knew from their high-school history book. “It is a reminder to all of us; there is no greater love than someone who is willing to lay down their life for somebody else,” said 20-year Marine Corps veteran Michael W. Green, former cemetery superintendent. One selfless warrior buried here is bomber Captain Foy Draper from California (plot F, row 10, grave 7), verification that America gave her finest. A graduate of USC and gold medalist at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Draper was part of the historic four-man Team USA that set the new world record with sporting legend Jesse Owens in the 4 x 100 meter relay. But every one of our heroic sons here has a story to tell, including the 240 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified; their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.”

In exotic North Africa, this ABMC memorial park was permanently established in 1948 upon a plateau above the Bay of Tunis and Mediterranean Sea in a historically fertile part of the region formerly known as Roman Carthage, founded in 29 B.C. by Emperor Augustus. Even today, vestiges of Roman dwellings and roadwork still remain only a few hundred meters from the cemetery. Much closer, eucalyptus and acacia and pine trees frame the memorial park; Indian laurel and California pepper trees line the walkways. Made of Roman travertine marble imported from Italy, the visitors’ building is on the left after passing through the cemetery entrance gate. Inside, a 2,000-year-old Roman mosaic donated in 1959 by the then-president of Tunisia hangs on the interior wall. Outside, a feminine sculpture symbolizing Honor stands at the edge of a reflecting pool overlooking the vast symmetric rows of white-marbled crosses. She holds a laurel branch to bestow upon those who sacrificed their lives in the struggle for freedom. An inscription reads: “HONOR TO THEM WHO TROD THE PATH OF HONOR.” Intersecting the nine plots of headstones are four bubbling fountains bordered by the fragrant flora of rosemary, oleander, and pink geraniums forming small but welcoming oases in the desert climate. Beyond Honor begins the 364-foot-long Wall of the Missing bearing the names of 3,724 comrades to be remembered. The battles in which they fought—Oran, Casablanca, Algiers, Kasserine, Sicily, Ploesti—can be found along the wall engraved on oak-leaf wreaths made of Bianco Caldo stone from Foggia, Italy. The path concludes at the memorial building, which contains the chapel outfitted with Moroccan cedar (ceiling), walnut (pews), bronze (doors), Carrara marble (altar). Nearby, impressive wall maps made of colorful ceramic tiles illustrate American military operations across North Africa—from the “Torch” landings in Morocco through Algeria to Tunisia, November 1942 to May ’43.

Historically, the cemetery sits near the ancient town of Carthage, dating from 800 B.C., once the battlefield of the Third Punic War (149-146 B.C.) when Romans sacked the African metropolis and sold the survivors into slavery. World War II buffs will remember the beginning of the movie “Patton,” when the general diverted his driver off the path in search of the battlefield. The driver insisted the Americans and Germans clashed farther ahead. Patton found his battlefield, where the Carthaginians fought the Romans more than 2,000 years prior. Patton said, “I was here.”

To get there; the cemetery (Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, closed weekends as well as on U.S. and Tunisian holidays) is situated 16 km east of Tunis, the capital city of Tunisia, which is some 180 km southwest of the Italian island of Sicily, across the Mediterranean Sea. Taxis are readily available from downtown Tunis or the airport (9 km from cemetery). Railers, other than a taxi, consider riding the commuter train (“La Marsa”) from Tunis to Amilcar station; from here it’s a 5-min walk to the cemetery.

![]()

PHILIPPINES

22) Manila American Cemetery

Nearly the size of Arlington National Cemetery (200 acres), Manila American Cemetery is the largest burial

ground of U.S. military personnel outside of the United StatesAt Manila American Cemetery, 152 acres in size, 17,191 heroes rest peacefully—most of whom lost their lives while fighting in New Guinea and the Philippines. Nearly the size of Arlington National Cemetery (200 acres), Manila American Cemetery is the largest burial ground of U.S. military personnel outside of the United States. Among the thousands of patriots interred here, there are 29 Medal of Honor recipients (compared to 46 from WWII at Arlington), and 20 sets of brothers who rest side by side. Additionally, there are 3,744 unknown servicemen whose remains could not be identified, their headstones read: “HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD.” Not included with the aforesaid losses are the names of a staggering 36,286 missing comrades engraved on the memorial building’s support pillars; among their number are all five(!) Sullivan brothers from Waterloo, Iowa (pictured in the slider at the top of the page). An inscription reads: “SOME THERE BE WHICH HAVE NO SEPULCHER; GRANT UNTO THEM O LORD ETERNAL REST WHO SLEEP IN UNKNOWN GRAVES.”

Landscaped on a prominent plateau boasting tremendous panoramic views over the Philippine capital and Laguna de Bay, the lowlands to the mountains, and beyond to the South China Sea, Manila American Cemetery is designed spherically with 11 extensive burial plots coiling around the open-air memorial building situated on high ground marking the core of the necropolis. In simpler terms, if you think of the 11 plots as forming the centric rings of a dartboard, it’s easy to picture the cemetery’s layout, with the bull’s-eye being the memorial. Consisting of two hemicycles, like half-moon structures, the memorial buildings are enormous, grand architectural monuments, crowning the cemetery. From the entrance gate and visitors’ building, a tree-lined walk climbs through the field of honor to the memorial, on which its giant pillars made of Italian marble from Bari are more than 36,000 engraved names of the missing, arranged in alphabetical order according to the four branches of the Armed Forces. Within the west hemicycle are the missing from the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps and etched along the frieze are the significant battles in which they fought, such as: CORAL SEA, LEYTE GULF, GUADALCANAL, PELELIU. Within the east hemicycle are the missing from the U.S. Army, Army-Air Force, Coast Guard as well as some from the Marine Corps and again carved along the frieze are the significant battles in which they fought, such as: BATAAN, CORREGIDOR, BURMA, BISMARCK SEA, MANILA. Highlighting these battles and more, 25 large wall maps made of rich mosaics neatly illustrate American military operations in the whole of the Pacific theater. Towering 60-feet-high between both hemicycles, the memorial chapel preserves a place of solitude and prayer. On the chapel’s rear (south) facade is the inscription: “TAKE UNTO THYSELF O LORD, THE SOULS OF THE VALIANT.” Sounding heavenly strains across the fields of white-marbled crosses, the chapel carillon chimes daily every half hour until 17:00, when it concludes with the national anthems of both the Philippines and the USA, followed by a rifle volley then Taps: “Day is done, gone the sun. From the hills, from the lake, from the skies. All is well, safely rest, God is nigh ….”

To get there; the cemetery (daily 9:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is situated in Global City, Taguig, within the former confines of U.S. Army Fort William McKinley, about 6 miles southeast of downtown Manila. It can easily be reached from the city by taxicab. Drivers, from Manila take the ring road Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) to McKinley Road straight up to the cemetery. From Manila International Airport, connect onto Lawton Avenue up to the cemetery.

End of World War II cemeteries

That’s a wrap, folks! I hope you enjoyed reading about our gallant sons and daughters and now have a desire to visit an ABMC memorial park overseas. Please tell your friends and family; let’s get them involved too.

Click to go to Lest We Forget: World War One

Click to go to the introduction of Lest We Forget

![]()

The final two ABMC cemeteries are located south of the U.S. border and remember past conflicts with Latin America.

23) Mexico City National Cemetery

Many young American officers who fought valiantly together here were later to become renowned figures in

history as they fought against one another in the next warAt Mexico City National Cemetery, 1 acre in size and established in 1851 (but closed to further burials since 1923), the unidentified remains of 750 U.S. veterans of the Mexican-American War (1846-48) were collected from the battlefield and buried here in a common grave beneath a spire-shaped monument. A number of the war dead are U.S. Marines who fought in the epic Battle of Chapultepec, instrumental in the defeat of Mexico City. These warriors are immortalized in the opening line of the Marines’ Hymm “From the Halls of Montezuma…”, referring to the Marines who stormed Chapultepec Castle, Mexico’s West Point equivalent, September 13, 1847. Besides the Hymm, Marines honor their fallen number at Chapultepec via formal couture—the red stripe worn on the trousers of their Dress Blues is commonly known as the “blood stripe” to remember their immeasurable sacrifice on the fortified hill above Mexico City.

Additionally, the cemetery contains the graves of veterans from the American Civil War. It was here on this tropical garden site in the heart of Mexico City that 2nd Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant first directed combat troops during the Mexican-American War. Many young American officers who fought valiantly together here were later to become renowned figures in history as they fought against one another in the next war, such as Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant, “Stonewall” Jackson, James Longstreet, and George Pickett (of Pickett’s Charge fame at Gettysburg).

To get there; the cemetery (daily 8:00-17:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) is located at 31 Virginia Fabregas, Colonia San Rafael, 3 km west of the Metropolitan Cathedral, barely 2 km north of the U.S. Embassy.

24) Corozal American Cemetery

At Corozal American Cemetery, 16 acres in size, there are 5,490 Americans and others interred here in this tropical palm-tree lined memorial park, dedicated in 1914. Many are U.S. military servicemen while many others contributed to the construction, operation and security of the Panama Canal. In agreement with the Republic of Panama, care and maintenance of the cemetery in perpetuity was assumed by the ABMC in October 1979. The cemetery (daily 8:00-16:00 except closed December 25 and January 1) and visitors’ building (Mon-Fri 8:00-16:00) are located about 5 km north of Panama City, Republic of Panama, just off Avenue Omar Torrijos Herrera between the Panama Canal Railway train station and Ciudad Del Saber (formerly Fort Clayton). Drivers, turn right on Calle Rufina Alfaro at the Crossroads Bible Church and continue about half a mile to the cemetery. Railers, taxi and bus service to the cemetery is available from Panama City.

(Last updated January 2017)

Whilst I am grateful to all those who served and fought in WW2, Yet, may I ask some seventy years later the question “What would have happened if nothing had been done, no ‘reply in kind’ revenge wars were fought,” and diplomacy was used to settle political differences between nations, I claim Japan would not have invaded America, the Germans would not have invaded Britain, and the savings in lives lost and wartime goods, weapons, jobs and war materials alone would have been adequate compensation. I am certain that I am not the first person to state wars accomplish nothing, they have no value and are a disgrace to mankind. R Wilson, England. August 2021.

Thank you very much for the invitation :). Best wishes.

PS: How are you? I am from France 🙂

My father, West Point 1918, headed the U. S. Army’s American Graves Registration Command (AGRC) in Paris (1947-1950). At the time of his arrival, the U.S. dead of the European Theater were resting in 37 temporary cemeteries scattered throughout the Continent. The next of kin were given the choice of having their loved one returned to the U.S. or buried in Europe. Under Dad’s command, more than 80,000 deceased heroes of the European Theater were returned home. Approximately 60,000 others were buried in ten permanent American military cemeteries on the Continent, which were being graded and constructed by his command. All but one were built on the site of a former temporary cemetery. (More information about this subject is contained in a biography I wrote about my dad, and it’s on Amazon: “A Salute to Patriotism: The Life and Work of Major General Howard L. Peckham,” by Jean Peckham Kavale.)